|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Amigos w/ Common Interests

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<<

View Prev Image

|

|

|

|

View Next Image >>

|

Category: Food and Drink |

|

|

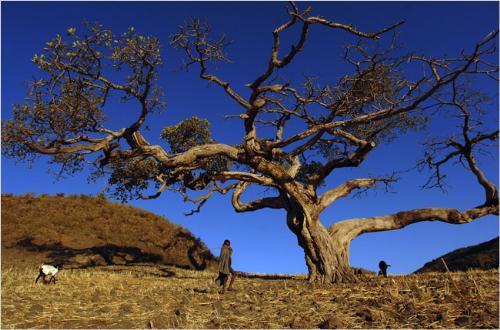

Ethiopia - where they must be strong to work. Malnourished and brain damaged chiukldren survive, but what of the future?

PHOTO NY TIMES

PART 3 of 3

Wondewosen Fekadu is the headmaster at Shimider Primary. Mr. Fekadu worked last year in Tseta, a lowland village where families eat better and drink milk. The difference in their students, he said, is striking. “Children there are relatively smarter and more active,” he said. “There are students here who are up to fourth grade and they cannot even read and write, even attentively following the classes.”

Three of Mrs. Gebeyew’s children attend Shimider Primary. Mogus, a 10-year-old third grader, is three and one-half feet tall — wide-eyed, sweet and flummoxed by academics.

“He’s on the poor level — very slow,” his teacher said. “He doesn’t give attention when I’m teaching. He doesn’t concentrate.” In a classroom of 60 children, Mogus ranks 46th.

Mulu, 13, her ribs prominent through rips in her green school dress, races from home to get to her beloved third-grade class. But Mulu is 47th in a class of 60.

Fifteen-year-old Yirgalem, about two inches taller than Mulu, has a teenager’s diffidence toward school. “It’s not that tough,” he said. His second-grade teachers differ. “When he comes to school, I don’t even think his mind is normal,” one of his teachers, Amelework Ejigu, said.

There is great promise that this region’s future youngsters will not be hobbled by mental disabilities. Virtually all nutritional deficiencies can be easily and cheaply prevented, sometimes for pennies per child, through programs like universal salt iodization, fortification of flour and semiannual doses of vitamins.

Such efforts already are under way in some nations, and they are a foundation of most United Nations children’s programs. But in just as many places, they remain a promise.

At Tefera Hailu Memorial Hospital in Sekota, across a mountain from Shimider, the nutrition ward’s 10 beds are filled with worried mothers and shrunken babies. Among them are Adna Berhanu and her 5-month-old son, Agnecheu.

Mrs. Berhanu’s huge goiter is decorated with blue tribal tattoos. Her skeletal baby is severely iodine deficient, surely impaired for life should he survive.

Although iodine deficiency is endemic in Amhara Province, “I’ve been here a year, and we have no iodine in this ward,” the nurse on duty said. Beyond a blood test to estimate iron content, the attending physician said, no one even analyzes children’s nutritional status. Such tests, he said, are luxuries.

“We focus on saving lives; that’s our long-term focus,” he said. “We can’t focus on what happens to them afterward.”

Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|