|

|

|

Amigos w/ Common Interests

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<<

View Prev Image

|

|

|

|

View Next Image >>

|

Category: Food and Drink |

|

|

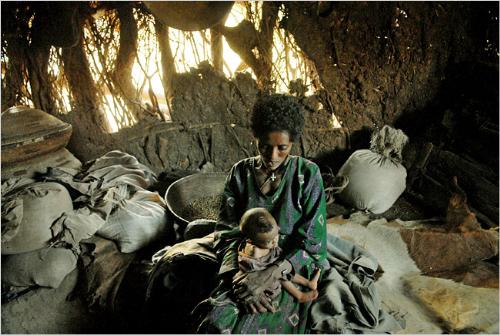

This woman and child aree shown in their hut with the WHOLE of their food until Spring

PHOTO NYTIMES

PART 1 of 3

December 28, 2006

Malnutrition Is Cheating Its Survivors, and Africa’s Future

By MICHAEL WINES

SHIMIDER, Ethiopia — In this corrugated land of mahogany mountains and tan, parched valleys, it is hard to tell which is the greater scandal: the thousands of children malnutrition kills, or the thousands more it allows to survive.

Malnutrition still kills here, though Ethiopia’s infamous famines are in abeyance. In Wag Hamra alone, the northern area that includes Shimider, at least 10,000 children under age 5 died last year, thousands of them from malnutrition-related causes.

Yet almost half of Ethiopia’s children are malnourished, and most do not die. Some suffer a different fate. Robbed of vital nutrients as children, they grow up stunted and sickly, weaklings in a land that still runs on manual labor. Some become intellectually stunted adults, shorn of as many as 15 I.Q. points, unable to learn or even to concentrate, inclined to drop out of school early.

There are many children like this in the villages around Shimider. Nearly 6 in 10 are stunted; 10-year-olds can fail to top an adult’s belt buckle. They are frequently sick: diarrhea, chronic coughs and worse are standard for toddlers here. Most disquieting, teachers say, many of the 775 children at Shimider Primary are below-average pupils — often well below.

“They fall asleep,” said Eteafraw Baro, a third-grade teacher at the school. “Their minds are slow, and they don’t grasp what you teach them, and they’re always behind in class.”

Their hunger is neither a temporary inconvenience nor a quick death sentence. Rather, it is a chronic, lifelong, irreversible handicap that scuttles their futures and cripples Ethiopia’s hopes to join the developed world.

“It is a barrier to improving our way of life,” said Dr. Girma Akalu, perhaps the nation’s leading nutrition expert. Ethiopia’s problem is sub-Saharan Africa’s curse. Five million African children under age 5 died last year — 40 percent of deaths worldwide — and malnutrition was a major contributor to half of those deaths. Sub-Saharan children under 5 died not only at 22 times the rate of children in wealthy nations, but also at twice the rate for the entire developing world.

But below the Sahara, 33 million more children under 5 are living with malnutrition. In United Nations surveys from 1995 to 2003, nearly half of sub-Saharan children under 5 were stunted or wasted, markers of malnutrition and harbingers of physical and mental problems.

The world mostly mourns the dead, not the survivors. Intellectual stunting is seldom obvious until it is too late.

Bleak as that may sound, the outlook for malnourished children in sub-Saharan Africa is better than in decades, thanks to an awakening to the issue — by selected governments, anyway.

South Africa provides nutrient-fortified flour to 30 million of its 46 million citizens. Nigeria adds vitamin A to flour, cooking oil and sugar. Ethiopia’s government hopes to iodize all salt by year’s end. United Nations programs now cover three in four sub-Saharan children with twice-a-year doses of vitamin A supplements.

Ethiopia may, in fact, have the most comprehensive program in all Africa — a joint venture with United Nations agencies that regularly screens nearly half of its 14 million children under 5 for health and nutrition problems. Since 2004, the program has delivered vitamin A doses and deworming medicine to 9 in 10 youngsters, vaccinated millions against childhood diseases and delivered fortified food and nutrition education.

Unicef’s Ethiopia representative, Bjorn Ljungqvist, said the effort sprang from a disastrous 2003 drought in which global aid agencies fed 13.2 million Ethiopians — the most costly aid undertaking ever in Ethiopia. When the aid effort ended, he said, international donors and government officials decided that “we have to ensure that we don’t get into this situation again.”

The program may be a model for Africa: similar ones try to improve youngsters’ health, but none, Dr. Ljungqvist said, addresses the nutritional deficiencies that leave children with lifelong disabilities. The effort saves 100,000 lives a year, by Unicef estimates. And because it focuses not just on handouts, but on preventive care and nutrition education, the effects could be lasting.

Beyond that, as African nations develop Western-style mass markets, with brand names and national distribution networks, sales of vitamin-fortified foods are slowly becoming common in urban areas, just as in the West decades ago.

But much of the continent has far to go.

CONTINUES NEXT 2 IMAGES |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|